Xinhua, the Chinese state news agency, reported on Tuesday June 21st that non-structural, peripheral parts of China’s Three Gorges dam had buckled during the weekend’s severe flooding. Controlling the country’s might Yangtze River, which crested from flooding on Saturday, the Three Gorges Dam is the world’s longest.

Since June, flooding along the Yangtze and its tributaries has displaced 1.8 million people and caused US$7 billion (49 billion yuan) in losses. The heavily populated southeast was once the center of Chinese agriculture, but government planning has changed key growing areas.

Other Recent China Flood Control Measures

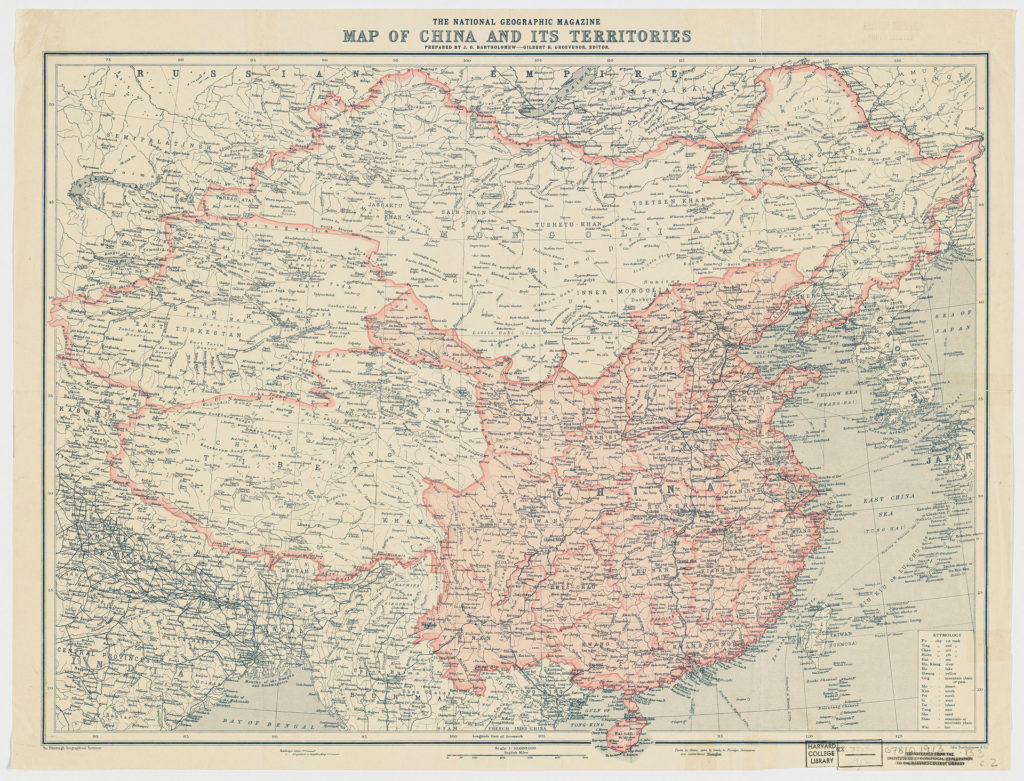

On Sunday, authorities in China’s central Anhui province blasted a dam on the 100-mile long Chu River, a tributary of the Yangtze, in hopes of easing floodwaters. The Chu flows into the Yangtze near Nanjing, 150 miles northwest of Shanghai and the nation’s capital during part of the Ming Dynasty. Meanwhile, flood warnings were also raised for the Huai River, in the eastern part of the country. In 1911, flooding in both the Huai basin and along the Yangtze caused major flooding. An estimated 70% of the rice crop was destroyed and famine followed.

Summer is Flood Season

China’s flood season runs from April through September, when monsoon season hits the southern part of the country. While this year’s flooding has been concentrated, so far, in July, other river disasters have come later in the year. The 1887 Yellow River flood, which killed as many as 2 million people, crested at the end of September. The famine-bearing 1911 Yangtze flood hit its height in August. Up to 4 million people lost their lives.

Will China’s Agriculture Planning Blunt Flooding’s Crop Impact?

The long-term goal of Chinese agricultural policy is to make the country as food-sufficient as possible.

By 1949, when the Communist Party of China took control, almost all of China’s arable land was farmed. The country since often had national agricultural planning, prescribing what can be planted where. This led to improvements in some areas, but also to disasters such as the 1959-61 famines during the The Great Leap Forward.

Liberalization in the 1980s lifted controls on farm prices and led to small farmers being able choose what they planted. However, little could be done about the lack of arable land. Today, only about 14% (134 million hectares) of China’s land can produce crops. Urbanization and polluion have decreased arable land available in the traditional southeastern and central agricultural heartland.

In 2017 and again in 2019, new policy documents advocated pooling of land resources to encourage larger-scale agriculture. As part of the plan, China’s agricultural bank offered support for larger scale agricultural infrastructure. A subsidy of up to 30% of the cost of large agriculture machine also became available. This helped support agricultural development in “less populated” parts of the country.

Subsidies by Province Encourage Production in the North and West

These policy documents also proposed that certain regions be designated for the growing of specific crops. The areas would then be targeted for subsidies and technical assistance. An example of this is northeastern Heilongjiang province’s support for soybean growing. To encorage the switch from corn to soybeans in 2018, farmers received 75% more in subsidies than farmers in traditional soybean growing areas.

Rice production has also shown a dramatic shift north, thanks to government encouragement. As industrialization grew, rice production in water-abundant coastal provinces like Guandong decreased. In 1995, the northern provinces of China only produced 7.5% of the country’s rice crop. By 2018, northern Heilongjiang province alone produced over 12.5% of China’s homegrown rice. Hunan, watered by tributaries to the Yangtze, is traditionally the most productive province for rice. In 2018 Hunan’s harvest was beaten in size by Heilongjiang’s abundance.

Cotton production, too, has moved according to government supports. In 2000, the western province of Xinjiang produced 32% of China’s cotton, today it’s around 80%. Henan and Shandong, on the Yellow River, and Hubei, Anhui and Jiangsu, on the Yangtze, were responsible for over 43% of cotton in 2000. In 2018, together they produced less than 10%.

What Else Can Hit Chinese Agriculture This Summer?

The cotton crop in Xinjiang has yet to report impact from the locusts plaguing cotton crops in Pakistan in India. A BBC story says that the province will fight off the locusts with ducks.

The main Chinese cotton areas are outside the flood zones. The geographic shifts in production may have helped ameliorate some of the flooding’s agricultural impact on cotton and other crops, but there is still ten weeks until the end of September. The weather may hold the key to both production levels and commodity prices.