Faced with numerous challenges globally, this week the ICE Cotton No 2 futures contract bounced off the $0.60 level. In its latest outlook, the USDA estimated that global consumption of U.S. agricultural production dropped 15% in 2019-20. The collapse in cotton exports was bigger than that for other major agricultural commodities overall. Perhaps this is because cotton has no food industry support. People may change their diets, but they still must eat. Consumers can, however, stop buying clothes and new household textiles. Meanwhile, China’s recent US purchases are more than it needs for current operations and may be moved into the country’s reserve system. These bales could then be used to offset future purchases.

As with everything in 2020, many factors are playing into U.S. and global cotton prices. Let’s look at a country-by-country breakdown.

The Overall Market

While China and India are the world’s biggest cotton growers, the United States is the biggest exporter. China is by far the biggest cotton user (although not the largest importer), with India coming a distant second. US prices have rebounded from March lows, but its export sales have been flaccid. For the week of July 23, US cotton was sold to only 6 countries, with Vietnam the leading buyer.

Like many commodities, this market is dictated, to some degree, by Chinese concerns and actions. U.S. cotton is gripped by drought in key growing areas, but global circumstances make prices. Even low oil prices globally can impact cotton. Lower oil prices mean lower prices for the synthetic yarns that can replace cotton in a garment or other textile. In July 2019, cotton and Chinese polyester were only a few cents apart in price. This month, cotton cost almost twice as much. Three-quarters of Americans say that COVID-19 has to some degree impacted their finances. Final retail prices are now even more likely to dictate what yarns consumer fashion and textile brands use. Shoppers everywhere are more price-conscious, not just in the U.S.

India

With a 5% government increase in its minimum support price for cotton, India looks set for a bumper crop both this year and next. The Cotton Association of India increased its crop estimates for 2019-20 to 335 lakh bales, a jump of 8% on the previous year. (A lakh is a South Asian measurement denoting 100,000 of an item.) As of the end of July, government ministries held the planting area nationwide had increased by over 11% for 2020-21. USDA projections, however, see India’s production falling by around 7%.

At the same time, India’s estimated domestic consumption may be only 280 lakh, a fall of 15% from the previous year thanks to COVID-19. Prices in the open market have plummeted since the start of the epidemic and India’s spinning sector faces a contraction of 25% this year. The Cotton Corporation of India (CCI), a government entity, has bought approximately 1/3rd of the year’s production. CCI is looking to increase India’s exports to Bangladesh, the world’s largest cotton importer. It also is building a warehouse in Vietnam for Indian cotton to increase sales in that country. Vietnam is the world’s second-largest importer and India’s third-largest cotton market.

Locusts in Cotton Areas on the India-Pakistan Border

Pakistan is the world’s fourth-largest producer but production no longer meets the country’s manufacturing demand. Brazil, Spain, the United States, and India take up the slack. Issues with seeds and the inability to hedge crops successfully are some of the issues impeding Pakistan’s cotton expansion. Raw cotton exports for the first 11 months of FY20 decreased by 9.93% while yarn exports declined by 13.12%. Because prices have fallen and other crops are easier to grow, Pakistani acreage has declined by 1.3% this year, according to the Cotton Commissioner.

Pakistani cotton is grown in provinces along the border with India. It is here that the locust swarms that started in Africa have made their roost and continue to breed. In India, over a million acres have been sprayed to control the flying insects. So far, the Indian government says, there has been no major damage in Gujarat and Rajastan, the primary cotton areas. Because of incentives to abandon rice, India’s Rajastani farmers have increased cotton acreage this year.

Pakistan’s locust efforts have not been as co-ordinated, at times, and there are worries that the insect plague could lead to severe food insecurity. This month, China donated 12 agricultural spraying drones to Pakistan, along with technical assistance to operate them. A previous plan by a Chinese company to send 100,000 ducks to eat the Pakistani locusts was axed as unrealistic. The Himalayas separate India and Pakistan from Chinese territory and the mountains’ altitude and climate are not hospitable to locusts. The only locust route to China’s cotton-producing Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region would be through Kazakhstan.

Xinjiang, Uighur Rights, and the Chinese Cotton Supply

To those who follow current affairs, there may be no commodity as politically charged right now as Chinese cotton. The world’s second-largest cotton producer, China grows about two-thirds of what it needs to supply its textile and garment industries. Xinjiang province, in China’s west, now produces about 85% of the country’s crop, a substantial increase over the 52% Xinjiang produced in 2012. Since 2014/15, China has increased agricultural subsidies to Xingjiang, while cutting them to more populated provinces in the east, which had seen labor costs spike. Workers there prefer higher-paying manufacturing jobs over farming. Xinjiang’s dryer climate also had the advantage of fewer pest problems.

Xinjiang’s growing dominance is not just an agriculture story, however. The region’s growth is a prime example of politics and economics colliding or colluding, depending on your point of view. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), a quasi-state, quasi-military entity, was set up by Mao Tse Tung to “stabilize” the area. Xinjiang is peopled primarily by the Turkic-speaking, Muslim Uighurs, not Han Chinese, like most of the country. The XPCC serves as the equivalent of the regional government but it also runs businesses. XPCC brings in Han migrants to pick cotton, at rates higher than the local population, and sometimes gives them their own plots of land. It is in some ways the same economic strategy as that used to increase the Han population in Tibet.

Uighur Repression Impacts the Textile Trade

Meanwhile, economic expansion has not come without cost to some in the indigenous population. News articles and non-profit reports highlight the use of coerced labor in textile-related industries. The Chinese government aims to have 1 million textile jobs in Xinjiang by 2023. That would be around 10% of all textile-related jobs in the country.

Political dissatisfaction is rife in the local population, and drone footage of concentration or “education” camps was shown on the BBC. China denied the existence of such camps. Uighur workers were found by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute to have been sent to factories in other provinces. The conditions were likened to “forced labor.”

All this means that more pressure is being put on garment and textile companies globally to ensure that forced labor is not used anywhere in their supply chain. That includes the production of cotton. The U.S. State Department was stark in its July 1 Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory. “In addition to the forced labor present in the province, there is evidence of forced prison labor in the cotton, apparel, and agricultural sectors.”

THE US-CHINA TRADE WAR BOOSTED BRAZIL and AUSTRALIA

During the trade war, US cotton exports to China declined by almost 28% between 2017 and 2019. Australian and Brazilian cotton sales skyrocketed, with both countries more than quadrupling exports to China in 2018-19. Brazil, now the world’s second-largest cotton exporter, saw its overall cotton exports more than double between 2017 and 2020. The country’s exports to China trebled between the 2017/18 and 2018/19 crop years.

The new Australian dependence on cotton exports to China, however, recently took a nasty turn. Bankruptcy by a cotton importer in China has left the Australian cotton market reeling. Privately held Weilin Trade, which also had a cotton farm in Australia and processed cotton, had committed to buy up to half the Australian cotton crop for the 2019-2020 season. Plagued by drought for several years, this year’s crop was the country’s smallest in four decades. However, some analysts had predicted that next year’s crop would triple, thanks to increased rains.

What caused the firm’s collapse was both Covid-19 and Chinese textile companies’ belief that Australian cotton was too expensive after the drought. They switched to Xinjiang cotton instead. Australia is heavily dependent on exports to China, and policy, such as the development of Xinjiang, and politics have impacted the agriculture sector. Australian farming had been hit with Chinese export restrictions on beef and barley earlier this year. This came after the government called for an inquiry into the origins COVID-19. Unsurprisingly, after Weilin’s collapse, Australian cotton prices have tumbled.

United States

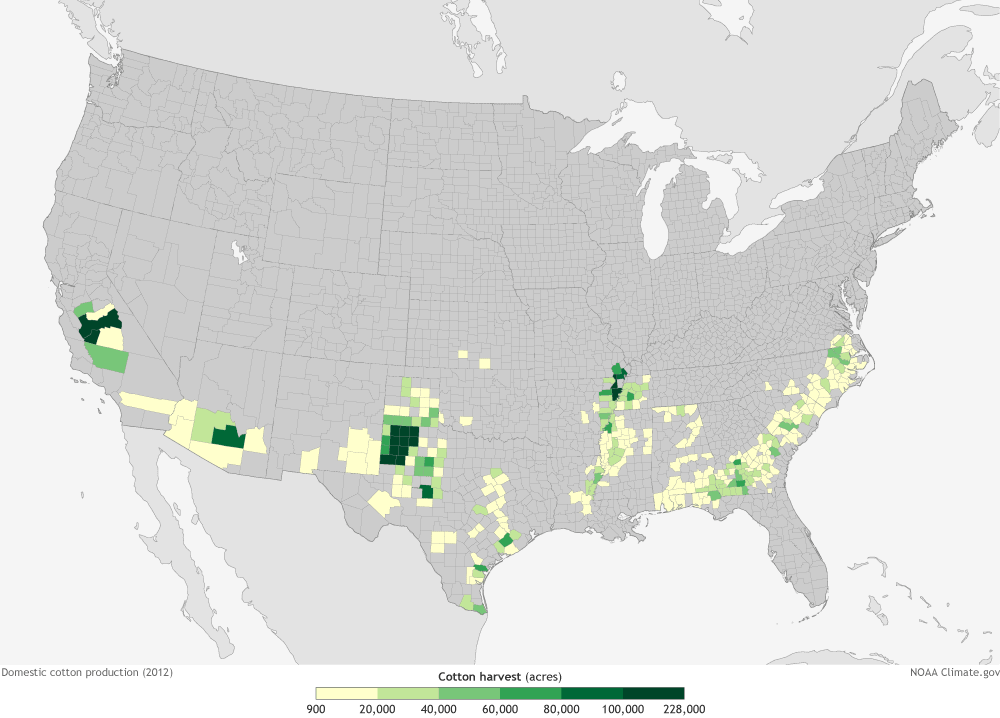

USDA 2020 cotton harvest predictions are now 12% below production for 2019, possibly with lower quality. The highest producing United States cotton counties are now primarily in the Southwest: Texas and Arizona. As previous Best Weather posts have pointed out, there has been a serious drought in the high producing West Texas areas.

As the world’s biggest exporting country, U.S. markets have been hit hard by COVID-19 related losses. California cotton farmers are planting an estimated 20% less land for 2021 harvest due to pandemic related losses. The Southeast is expected to sow 17% less acreage and the Delta region 22% fewer acres than in 2019. In the West, farmers are expected to plant 19% fewer acres than in 2019. This would be the lowest acreage in five years.

Which Way Will Cotton Go?

While US cotton farmers are decreasing acreage in light of 2020’s calumnies, Indian and Brazilian farmers have expanded. COVID-19 is continuing and most countries are unlikely to recover lost GDP for a while. With old stocks high and the expansion of foreign cotton acreage, U.S. and other cotton producers need luck to break out of the present trading ranges. Recently languishing in the upper-50s to mid-60s, ICE cotton seems unlikely to recover the summer of 2019 heights of 94.21 anytime soon. The one bright spot for non-Xinjiang cotton is the push for supply that can easily meet human rights production standards.